Belarus – Russia: Hunger games. The Kremlin’s price list

Anatoly Pankovski

Summary

The year 2021 saw a dynamic combination of three options of Belarus – Russia convergence and, consequently, the Kremlin’s support for the Alexander Lukashenko Administration with a pronounced momentary emphasis on one of them – constitutional reform, economic integration, or military cooperation. In an attempt to avoid significant concessions on these points, Lukashenko maneuvered in a narrow space shaped by both the Western political pressure and sanctions, and insistent ‘advice’ from Moscow.

The rapid deterioration of investment and transit opportunities and, therefore, weaker negotiation position in disputes with the ally actually turned the Lukashenko regime into a passive observer of a big integration game. Signs of a gradual erosion of the Belarusian sovereignty have become visible behind the political bargaining facade.

Trends:

- Moscow’s deep involvement in Belarusian affairs;

- Escalated integration games within the Belarus-Russia Union State;

- Pronounced emphasis on the militarization of relations with a clear prospect of Belarus turning into Russia’s military-strategic foothold;

- Significant increase in the trade turnover with outstripping growth of imports from the Russian Federation.

Three basic values: transit, integration, militarization

The year 2021 was a period of phenomenally active contacts between the Russian and Belarusian leadership, which is natural in the setting of the international isolation of Belarus and avalanching degradation of foreign policy alternatives. Contacts between the top leadership, interdepartmental meetings and consultations, including those under the auspices of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, CIS, Eurasian Economic Union and Union State, took place throughout the year. Lukashenko and Putin set the pace for the entire political establishment. They contacted dozens of times during the year, and met six times in person. Russia replaced its ambassador to Belarus twice in 2021. Boris Gryzlov, who arrived in Minsk on a new ‘special assignment,’ took over Yevgeny Lukyanov’s office.1

In retrospect, there were neither acrimonious disputes over price terms and volumes of oil and gas supplies, nor political flare-ups like in the previous years, including the first half of 2020. The past year may be written down in the history of the Belarusian-Russian relationship as relatively conflict-free, although tensions between the allies, which accompanied the hard political bargaining, remained.

Three basic scenarios for the preservation of the Lukashenko regime at Russia’s expense took shape by the end of 2020:

- economic integration under the aegis of the Union State of Russia and Belarus, which implies a convergence of macroeconomic policies, harmonization of tax and customs legislation, etc.;

- political (constitutional) reform, which would guarantee Russia continuity and expansion of its influence on Belarus through a redistribution of presidential powers in Belarus among a wider range of institutions;

- a closer military-strategic alliance than within the CSTO.

The above three scenarios are not mutually exclusive. There is always a dynamic combination of these options with an opportunistic emphasis on one of them.

Constitutional adjustments (the transit of power) and integration programs are associated with institutional changes. Political transit means a transition from an individualistic regime to a political system that implies a lesser concentration of powers, hence being unacceptable for Lukashenko.

Institutional changes through the implementation of Union programs do not suit Minsk either, because they imply a redistribution and streamlining of economic powers (including stronger private property protection) according to Russian models without guarantees of a stable economic rent for the ruling group.

Also, Minsk, perhaps, considered close military cooperation and the actual passing of the Belarusian armed forces under Russia’s control as the least harmless integration option. (Except for Alexander Nevzorov and some other observers, no one seriously talked last year about the coming war). It is a different matter that military cooperation did not directly affect other terms disputed by the parties (for example, energy or loans). Although Russia suggested that Belarus’ security and building of its army, were worth something in exchange, if not money, then at least something no less substantial.

Twenty-eight short paths (tangles of problems)

The bilateral agenda in late 2020 and early 2021 was largely defined by the topic of constitutional reform. The configuration of the bilateral bargaining changed rather quickly, though, and the topic of integration came to the fore again.

Lukashenko revisited the topic once again in February 2021. He said that the parties only had 6 or 7 integration roadmaps (out of the 33 stipulated by the agreements) to finalize. For comparison, there were one or two unfinished maps out of 31 a year before. By the time of the September meeting between Putin and Lukashenko, the number of roadmaps increased to 28 and they were renamed “union programs.” Their list was finally published on the website of the Russian government.2

This package was finally signed on November 4, after which the integration activity slowed down drastically. After the approval of the integration decree, no noticeable progress in the convergence of the economies was made that year.

Summing up the preliminary agreements and actual circumstances of the integration process, its overall results can be described as follows:

- An agreement on the unification of the Russian and Belarusian gas markets was announced. It is expected to be signed before December 1, 2023. The parties also plan to establish a single oil and electricity market. This looks very tempting for Minsk, but the final terms of the ‘merger’ are not entirely clear yet. In 2021, Belarus failed to achieve substantial concessions on oil and gas. The country was buying gas at the price of the previous year (2020), and at the price of 2021 in 2022 (USD 128.5 per 1,000 cubic meters). The situation with gas transit went worse: the transit capacity was considerably higher than the actual piped volume, after the Nord Stream 2 was launched, so Belarus had to cover the difference at its own expense. Gas transit through Belarus in the fourth quarter of 2021 decreased from nine to two billion cubic meters.

- The maximum amount of the loans, which Belarus might count on in the period from September 2021 to the end of 2022 were expected at USD 630-640 million, according to Putin. Later, Standard and Poor’s linked this money with a partial compensation for Belarus’ losses from the tax maneuver in the Russian oil sector, which was neither confirmed, nor denied. In the first half of 2021, Minsk initiated negotiations on a USD 3 billion loan through the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development, and then, later that year, requested half a million more (USD 3.5 billion), but was turned down.

- The transport-logistic dependence on Russia is an inevitable effect of the serious quarrel with the West. Russia reap dividends from the isolation of Belarus, at least when over-executing the plan to redirect Belarusian oil products and then fertilizers to Russia’s northern ports. As a result of the air blockade imposed in April 2021, the Russian airspace became the only option for Belarus. Minsk hoped in vain that Russia would fully compensate for the losses of Belavia by expanding flights of the airline.

- There was nothing new in the thesis about joint defense against external threats, given that a ‘joint defense center’ was already there, joint exercises were held, etc. What was new is that regional context has changed, and Russia began making aggressive plans.

- Other agreements concerned mutual payments and integration of the currency systems under the decree on integration, which still remains a phantom, because even the negotiators admit that they are not yet ready for this transition. Many other agreements on the harmonization of the tax systems, equal economic and social rights and opportunities for Russians and Belarusians in the Union State, common industrial policy, reciprocal access to public procurement, state-guaranteed order, etc. do not go beyond mere declaration either.

Elements of political transit

Early in the year, Lukashenko reiterated his interest in political reform, and, on March 15, he issued a decree on a constitutional commission primarily tasked to map out amendments to the Constitution and ensure their “nationwide discussion”.

In fact, Lukashenko was rather reluctant to talk about constitutional amendments, choosing to play for time and fix the status quo in the future constitutional referendum. He more and more often called the possible amendments “corrections”, emphasizing their insignificance. The authorities published the final draft of the new constitution as late as the end of the year, and no significant changes were made during the fictitious “nationwide discussion”.

Some adjustments to the institutional design were made with the direct involvement of Russian security services when it came to the power transfer mechanisms.3 After the “detection” of the failed assassination attempt on Lukashenko, he issued a decree that stipulates that in the event of his violent death, the Security Council chaired by the prime minister would take over his powers with the simultaneous introduction of a state of emergency or martial law.4 This is supposedly meant to secure the heads of the law enforcement agencies, guarantee that Lukashenko’s entourage would retain their positions, and ensure that the Kremlin maintains partial control over the internal political situation during a transition period.

Sketches of the “hybrid warfare”

It would seem that only two convincing arguments were initially used in the disputes and bargaining with the Kremlin: constitutional reform and economic integration. However, as soon as early March, at a meeting on Belarus – Russia cooperation, Lukashenko put an emphasis on militarization of Belarus, defense cooperation with Russia, and establishment of an anti-Western axis.

Defense cooperation was on the agenda throughout the year. State propagandists dwelled on an imaginary hybrid war with the West in general, and Belarus’ neighbors in particular (the Baltic States, Poland, and Ukraine).

In summer 2021, Belarus put one more argument into circulation: the migration crisis at the western border of the Union State, which looked like Minsk’s desperate attempt to open communication channels with the West, resume the geopolitical swing, and, by this means, obtain some more chips in disputes with the Kremlin. The migration crisis was complemented with the Belarusian-Russian West 2021 military exercise. Following the Lukashenko-Putin meeting held at the end of December 2021, the allies in the future anti-Ukrainian axis announced the new Union Resolve 2022 exercise.5

Through the entire year, Minsk actively sought to escalate relations with the West in such a way that it would simultaneously increase tensions between the West and Russia. The result of this strategic effort was already visible in the second half of 2021, and manifested itself in abundance in February 2022. By the end of the year, Belarus de facto transformed into Russia’s military-strategic foothold.

Trade and economics

The Belarusian-Russian trade turnover grew markedly in value terms by 35% in 2021 against 2020 thanks to the so-called “foreign economic miracle” (Table 1), most evidently, the restoration of energy imports and exports of potash fertilizers and oil products amid rising prices of raw materials.

Figure 1. Exports and imports by aggregated product grouhs

Source: Belstat.

Leaving other roots of this phenomenon aside, the increase was short-term, and domestic demand and consumption in Belarus was in an apparent downward trend, according to economists.6

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | % against 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover | 27,533 | 26,114 | 32,424 | 35,561 | 35,552 | 29,667 | 40,053 | 135.0 |

| Exports | 10,398 | 10,948 | 12,898 | 12,986 | 13,569 | 13,157 | 16,392 | 143.3 |

| Imports | 17,143 | 15,306 | 19,599 | 22,619 | 21,982 | 16,510 | 23,661 | 124.6 |

| Deficit | 6,745 | 4,558 | 6,701 | 9,633 | 8,414 | 3,353 | 7,268 |

Table 1. Belarus – Russia foreign trade in commodities in 2015–2021, USD million7

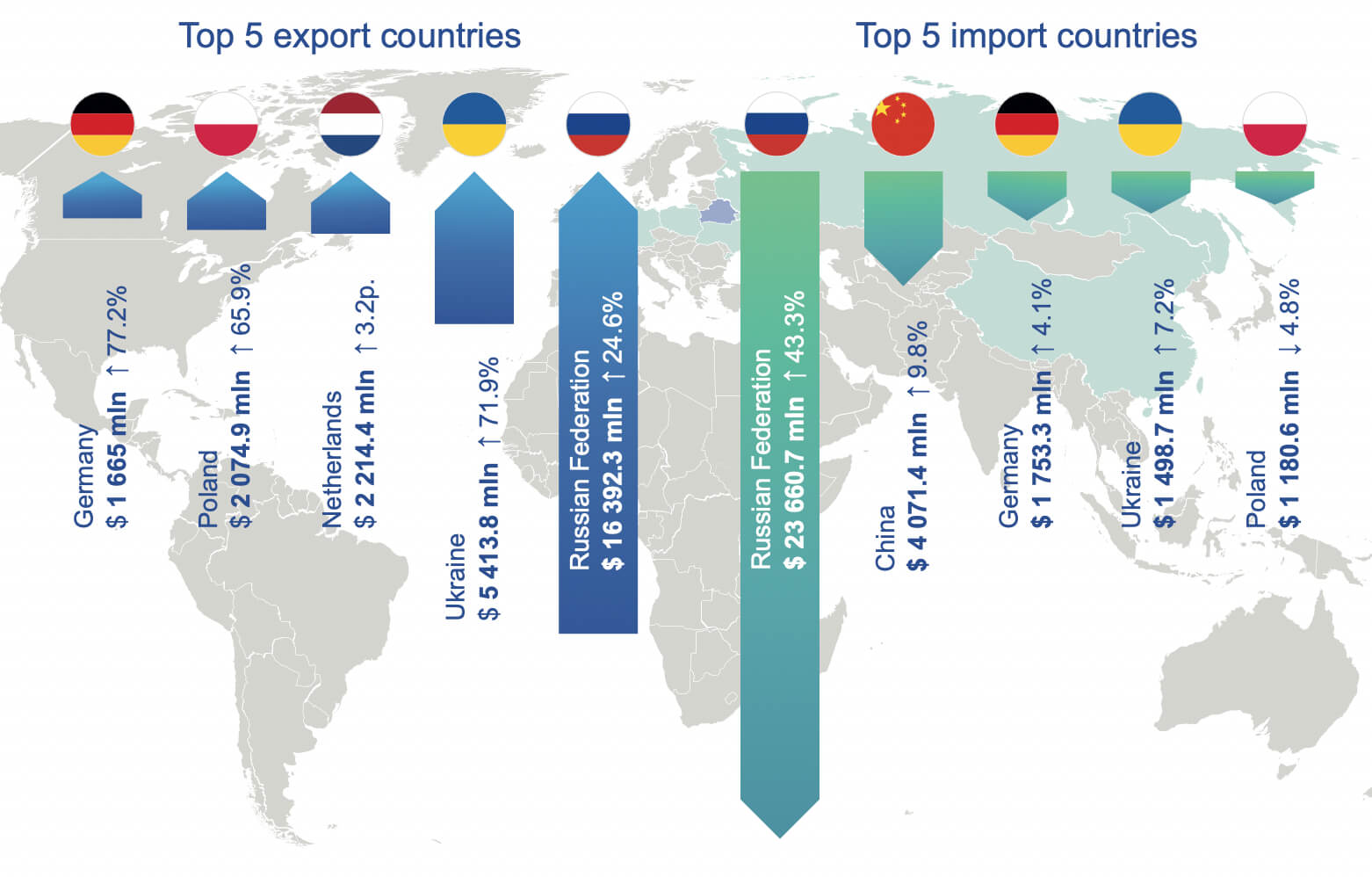

The trade turnover surpassed USD 40 billion for the first time in nine years. Belarusian exports to Russia totaled USD 16.39 billion, while imports from Russia stood at USD 23.66 billion, Belarus’ deficit thus only amounting to USD 7.27 billion8 (see Table 1, Figure 1).

The National Statistics Committee of Belarus (Belstat) stopped publishing reports on foreign trade in commodities under sanctions. The contribution of the oil component is evident in all three indicators (import, export, net). The increase in supplies of Belarusian foods and oil products to the Russian market is reflected in the increase in imports. According to the Belarusian embassy in Russia, 31 new commodity items were added to the list of exports to Russia in 2021, but the increase was not impressive in value terms (USD 0.6 million).9

As before, Russia remained the major and most important foreign economic partner of Belarus. In 2021, it accounted for 49.0% of Belarus’ commodity turnover: 41.1% of exports (45.1% in 2020) and 56.6% of imports (50.4% in 2020) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Exports and imports of goods country, 2021

Note. In 2021, export and import transactions were recorded with 206 countries. Goods were supplied to the markets of 172 countries, products were imported from 191 countries.

Source: Belstat.

Conclusion

The Russian invasion of Ukraine that began on February 24, 2022 is a “conservative revolution” in practice,10 a reaction to a series of political crises in Belarus, Kyrgyzstan (2020) and Kazakhstan (early 2022), and an attempt to prevent a collapse of the post-Soviet imperial complex with Russia in the center. The war highlights the key points of the Belarus – Russia relationship differently. Despite the high uncertainty, future political trends can be described as follows.

- “Smooth takeover”, i. e. the partial or complete transfer of some sovereign functions and infrastructure of Belarus as a state to Russia. In particular, this concerns transport and logistics capacities, information policy, defense and security, etc. Currently, Lukashenko has no control over the movement of the Russian military across the country, and he cannot make most decisions without taking into account the Kremlin’s opinion.

- For Minsk, the international isolation and sanctions, which tend to turn into a full-fledged economic blockade, mean an even greater dependence on Russian political elites, their decisions and fate.

- Russia’s economic assistance in the form of debt restructuring, super favorable regime for Belarusian enterprises, access to import substitution programs, more “optimized” prices of energy commodities, etc. could help the Belarusian economy, but the effects of these indulgences is very limited, and potential positive effects are strongly influenced by the situation in the Russian market.

- The constitutional referendum of 2022 will still be followed by further bargaining on the implementation of the union programs and economic assistance to the ally. The result of the referendum does not guarantee Moscow’s subsequent non-interference in the internal affairs of Belarus.

The Kremlin’s aid is not gratuitous, and there are things it values more than Lukashenko’s debt warrants. Turning Belarus into an external military-strategic foothold of Russia is one of the items on the Kremlin’s price list. The change in the geopolitical status of Belarus demonstrates one of the most dramatic metamorphoses in Eastern Europe of the past eight years.