Media: Ideological battlefield without prerequisites for development

Elena Artiomenko-Meliantsova

Summary

The 2020 trends in the Belarusian media field intensified in 2021. The entire system of independent media was destroyed, and the outlets engaged in covering social and political affairs were stripped of their legal status and their activities criminalized. In the meantime, state controlled media applied new propaganda approaches and new technologies.

While the state propaganda was broadcasted on official channels on a larger scale, the media uncontrolled by the state was losing access to official sources of information and forced out of the country, so the media’s public oversight and information security functions were largely undermined or discontinued.

Relative successes in the economy, which could revitalize the advertising market and, consequently, the financial standing of the media, cannot ameliorate the overall situation, since independent media’s infrastructure is destroyed.

Trends:

- Destruction of the independent media sector;

- New methods of state propaganda in the controlled media;

- Uncertainty in the advertising market and public relations.

Situation with independent media in Belarus

The large-scale state campaign aimed at sterilizing the media scene continued in 2021. The mass media, NGOs and those who dared to criticize official policies remained under massive pressure. The majority of actively working independent socio-political periodicals were forced out of the country. Although, according to the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), the number of detentions of journalists decreased from 481 in 2020 to 113 in 2021, the authorities managed to almost completely destroy independent media, and subjected many of them to criminal prosecution.

The BAJ reported criminal cases against 60 journalists in 2021, 32 of whom remained in custody as of the end of the year. Yekaterina Borisevich (tut.by), Yekaterina Andreyeva and Darya Chultsova (both Belsat) and Sergei Gordievich (1reg.by) were convicted in criminal cases; there were 146 searches of offices and homes of independent media journalists, mostly on suspicion of involvement in terrorist activities and/or organization and preparation of actions that grossly violate public order (sections 289 and 342 of the Criminal Code of Belarus).1

The authorities used the amended anti-extremist legislation to push independent media out of the legal field. Materials published by independent outlets were massively declared extremist, after which their websites and social media channels were blocked. Anyone who distributed such materials (including by reposting on personal pages in social media) face prosecution.

According to the Republican List of Extremist Materials, from 2008 to 2020, there were 172 court rulings to declare various materials extremist. The number of such rulings was over four hundred in 2021 alone. Alongside major independent media channels (tut.by and Nasha Niva among them), the same measures were applied to communication channels of opposition institutions, regional and local information channels and chat rooms. A number of large outlets, such as Belsat, Radio Liberty, BelaPAN news agency and their followers in social media, were declared extremist groups, membership in which is a punishable crime now.2

The Ministry of Justice filed a lawsuit to liquidate the Belarusian Association of Journalists, which worked in the field of research, support and development of the media in Belarus. In April 2021, Reporters Without Borders ranked Belarus 158th out of 180 countries in terms of the freedom of the press. Belarus was called Europe’s most dangerous country for journalists.3

Many outlets continue working from outside the country, but their effectiveness considerably decreased. Access to sources of information and opportunities to distribute their products are very limited, and there are few or no possibilities for self-financing. The outlets, nevertheless, retain a significant part of the Belarusian audience that finds technical ways to bypass the blockages.

New approaches applied by state-controlled media

Since independent media have been almost completely eliminated in Belarus, the operating conditions for the state media are changing noticeably. Given the challenges posed by the 2020 political crisis, dismissals of some state media employees for political reasons and invitation of Russian substitutes to Belarusian TV, approaches to the creation and promotion of the state media content have undergone certain adjustments. The authorities take a part of the media content and propaganda messages to social media, mostly Telegram. Official channels were opened there, and advertisements are posted in other media, including YouTube.

Socio-political programs hosted by Grigory Azarenok, Igor Tur, etc. are released on state TV channels. They are not pronouncedly propagandist, but rather a kind of artistic performances. New Belarusian propagandists often outstrip their Russian colleagues in terms of aggressiveness and sarcasm. For instance, Xenia Sobchak said in an interview with Avdotia Smirnova that she watches Azarenok, who is more expressive than Russian propagandists, and called it her guilty pleasure.4

The targets and indicators set in the Mass Information and Book Publishing Program were formulated in 2021 as follows: to achieve the state mass media’s confidence rating of 41%; self-financing of the state print media of at least 72%; to increase in the share of Belarusian-made programs on Belarusian TV to 31%.

Attempts to increase self-sufficiency of the media in order to reduce the budget spending on them has been a mass communication policy objective in Belarus for years. The above could help enhance sustainability of the media and ensure information security, but nothing suggests that this may be achieved any time soon, neither from the viewpoint of external economic and political conditions, nor in terms of policies towards independent media or available resources.

Spending on mass media

New state media approaches are reflected in – the public funding dynamics. In 2019, BYN 87.3 million were allocated from the national budget for television and periodicals, while in 2020, the amount increased to BYN 150.4 million (BYN 143.1 million for television and radio and BYN 7.3 million for periodicals), which was connected with that year’s election campaign. The spending in 2021 was planned at BYN 155.7 (BYN 133.9 million for television and radio and BYN 21.8 million for print media).5

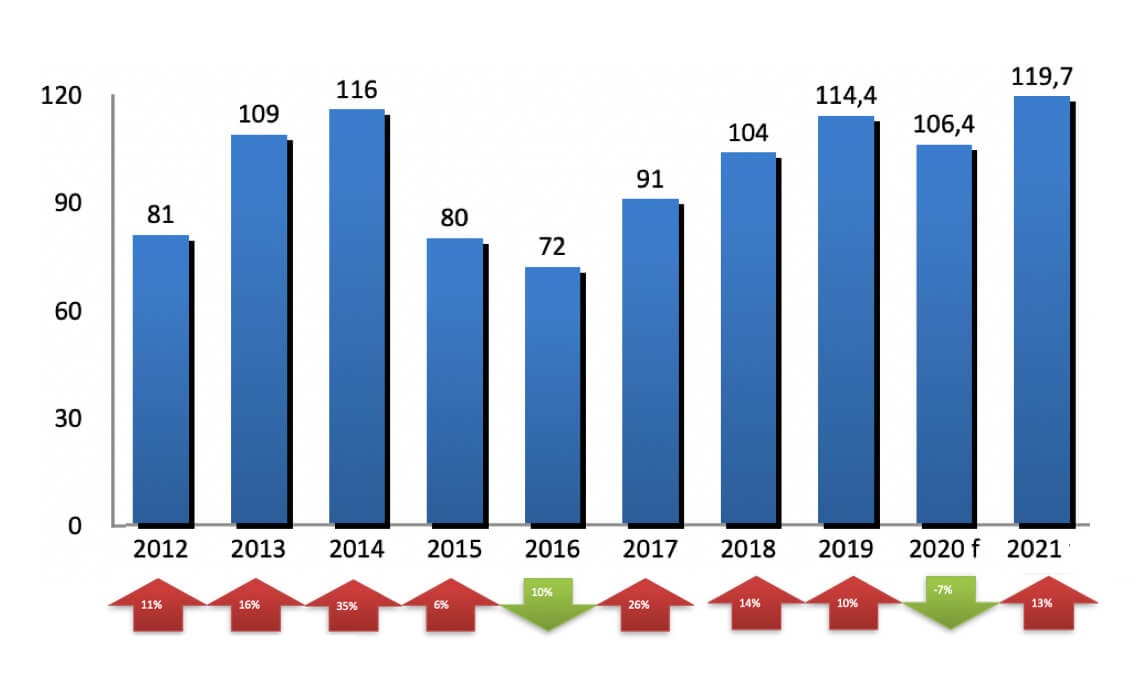

During the post-pandemic economic recovery period, the advertising market grew by 10–15% in 2021, according to preliminary estimates (Figure 1), largely thanks to the inflow of investments in online advertising.

Figure 1. Media advertising market dynamics in Belarus, 2012–2021, USD million

Source: Expert assessment by Alcazar, APO, Vondel-digital and WebExpert.

The expected Internet advertising market in 2021 is estimated at USD 50 million (USD 44.9 million in 2019–2022).6 However, 68% of the market falls on the advertising in search results and targeted advertising, rather than the mass media, which promotes online media development in a lesser degree. The destruction of independent media narrows the options for advertisers, since they lose partners for advertising and PR campaigns, which, consequently, reduces the budgets that could be channeled into the media market financing.

According to the available data for February 2021, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) accounted for 34% of the online media advertising (key players: Nestle, Mars, “Savushkin Product”); car sales – 16% (Avtopromservis, “Atlant-M”); financial services – 10% (MTBank, VISA); e-commerce – 9% (21vek. by); electronics – 9% (Samsung, Huawei); pharmaceuticals – 8% (Sandoz, Sanofi, KRKA); telecom services – 5% (A1, MTS).7 In television advertising in the second half of 2021, according to the Belarusian TV audience measurer Mediameter, the major advertisers were Mars (21,717 min), Jacobs (21,294 min), Nestle (19,719 min), A1 (16,236 min), PEPSICO (15,607 min), Coca-Cola (13,971 min), MTS (13,859 min), Procter&Gamble (11,401 min), L’Oreal (9,595 min), and Patio (8,663 min).8

This shows that multinational corporations that operate in the FMCG sector were among the main sources of funding for the media, including state TV channels, many of which declared their intention to abandon advertising on state TV in Belarus after the political crisis of 2020.

Media consumption by the Belarusian audience

Despite the growing influence of the Internet as a source of information, the coverage by Belarusian TV channels remains quite high, Mediameter says. In December 2021, the average daily rating of TV programs in Belarus stood at 15.98%, and the average daily media outreach at 62.95% of the Belarusian audience. Among the TV channels, the highest average daily outreach was achieved by ONT (27.10%), Russia-Belarus (24.56%), Belarus-1 (24.50%), NTV Belarus (23.30%) and CTV (17.92%). The monthly coverage of these channels is as follows: ONT – 78.98%; Belarus-1 – 76.51%; Russia-Belarus – 75.57%; NTV Belarus – 74.79%. In terms of monthly outreach, CTV (68.93%) was behind Mir (71.27%) and Belarus-2 (70.74%). The total monthly outreach by the measured TV channels was at 95.88% of the Belarusian audience.9

According to the Euroradio, Mediameter CJSC is most probably affiliated with the state. It surfaced after the state TV channels stated their dissatisfaction with their ratings.10 According to Chatham House, only 41.6% of the Belarusian audience obtains information from TV,11 while Baltic Internet Policy Initiative reports 30.9%.12

The above data have their methodological limitations. The data provided by Chatham House and Baltic Internet Policy Initiative only concern the Internet audience and, therefore, are understated. Mediameter’s data, on the other hand, is non-transparent, and is only collected with the help of peoplemeters in the households that have TV sets, and, therefore, the indicators are overstated.13

Among the preferred TV genres, films and TV series led with 40%, and entertainment programs with 25%. Belarusian viewers spent 16% of their time watching information programs, and 5% watching social and political programs.

Belarusian entertainment YouTube channels topped the list of the video content on the Internet. According to livedune.ru, World of Tanks Blitz was the most influential Belarusian channel in 2021 alongside Official Channel (665,000 subscribers, over 60 million views), Bready Bread (356,000 subscribers, 85 million views) and VERTEICH (551,000 subscribers, 98 million views) game channels. According to Baltic Internet Policy Initiative,14 in December 2021, Real Belarus (193,000 subscribers, 6.9 million views) was the most popular political channel. NEXTA Live totaled 157,000 subscribers and 4.7 million views; BELSAT News – 454,000 and 3.3 million, respectively; tut.by – 440,000 and 3.2 million; Danuta Hlusnia – 84,000 and 2.1 million; Malanka Media – 104,000 and 1.8 million; BalaganOFF – 88,000 and 1.6 million; VOT TAK – 359,000 and 1.5 million; Lukashenko’s Moustache – 60,000 and 1.4 million; ATN: News of Belarus and the World – 201,000 and 1.3 million.

Among the most popular Belarusian Telegram channels were NEXTA Live and NEXTA with 1.7 million and 412,000 subscribers, respectively (it should be noted that NEXTA Live was very popular with the Russian audience, and the administrators targeted it purposefully as well); Zerkalo | Novosti (409,000), Belaruski Hayun (392,000), Yellow Plums (“Tabloid Leaks” wordplay, 167,000), Belarus of the Brain (154,000), Unpleasant Channel (144,000), MotolkoHelp (126,000), Pool of the First (124,000) and Onliner (124,000).15

Given the above, entertainment and, to a lesser degree social and political content of both TV and new media channels is in greatest demand among the Belarusian audience. In the structure of the media consumption, independent resources are in the key positions in the new media. The fact that channels of the official media and government agencies were also in the top 10 indicates that the latter had joined the IT mainstream, and have their audience on the Internet.

The Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus and EcooM center say that in November-December 2021, the main sources of information about domestic events were the national television (22.0%), online media (21.7%) and social media (13.7%), the immediate social environment (10.9%), national newspapers and magazines (7.3%), local TV (6.6%), Russian TV (6.5%), local newspapers and magazines (6.5%) and national radio (4.2%).16

According to the sixth wave of the Chatham House’s poll (November 2021), Belarusians usually receive information from the Internet (69.2%), social media (67.7%), live communication (56.1%), TV (41.6%), messengers (38.1%), radio (14.8%) and printed periodicals (10.0%). Unlike EcooM, which only presents data as totals, Chatham House publishes raw data obtained from all respondents in XLSX/SAW formats for greater transparency.17

Andrei Vardomatsky’s Belarusian Analytical Laboratory says the state television and the Internet were approximately equal as news sources. When asked which channels had been important sources of socio-political information about developments in Belarus (as of March 2022), Telegram was named by 33.1% of respondents; state television – 32.1%; YouTube – 29.8%; Russian state television – 25.6%.

In terms of trust, the Belarusian Analytical Laboratory saw a long-term trend towards a decline in trust in the Belarusian official and Russian media. In December 2021, the index of confidence (trust/distrust ratio) of the Belarusian state-controlled media outlets was at 0.9 percentage points; Belarusian independent media – 18.2 p. p.; Russian media – 9.6 p. p.

Conclusion

The destruction of the independent media segment makes the Belarusian media unable to perform their socially significant functions. The forced relocation of most independent outlets in the absence of Belarusian advertisers (i. e. the impossibility to achieve self-financing) poses threats to information security.

New approaches applied by the state media to raise the degree of propaganda influence together with the use of new media channels can create an ideological alternative to non-state media. However, this does not solve the problem of building a national system of mass communication, which would ensure information security and make it possible for the media to perform their public monitoring functions.

Despite the adequate goals of state programs aimed at media self-sufficiency, a greater share of national content and higher public confidence, it is unlikely that they will be attained, given the current economic and political challenges and destroyed infrastructure of independent outlets. The Belarusian media space will continue to be a field of ideological struggle with great dependence on Russian media.