Education: Between export and sclerotization

Sviatlana Matskevich

Summary

In 2011, Belarusian education entered the phase of economic and administrative crisis that directly affected household education expenditure. Official accomplishment of quantitative targets does not ensure proper quality of education at all its levels.

The governments’ intention for Belarus to accede to the Bologna Process was the major event in the education sector last year that stirred up public discussion and provoked criticism of Belarus’ education policy in the civic and academic communities.

Trends:

- The quantitative and qualitative indicators showed a decline: the number of students and teachers goes down; the old structure is conserved and the ideological component remains unchanged.

- The Education Code effective since September 1, 2011 reinforced the administrative and authoritarian forms of education management and almost completely denies an opportunity of reforming.

- Still being a monopolist in education, the country leadership does not even try to imitate communication with other entities of the education process while, in response to the Education Ministry’s attempt to accede the Bologna Process, society demands real reforms rather than their imitation.

Economic crisis does not leave education unaffected

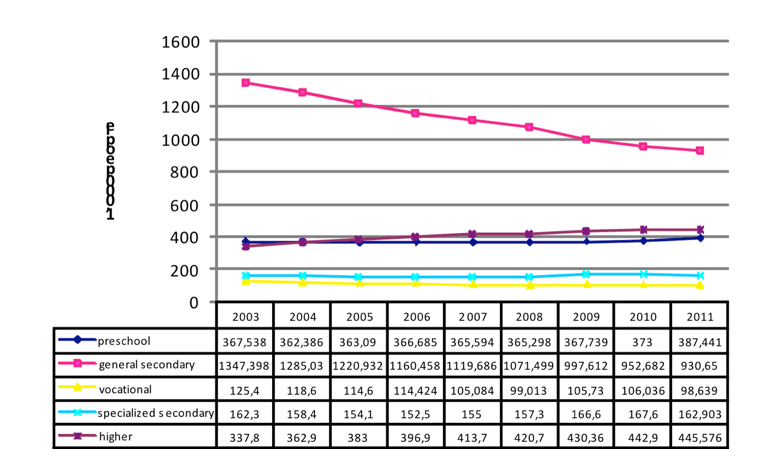

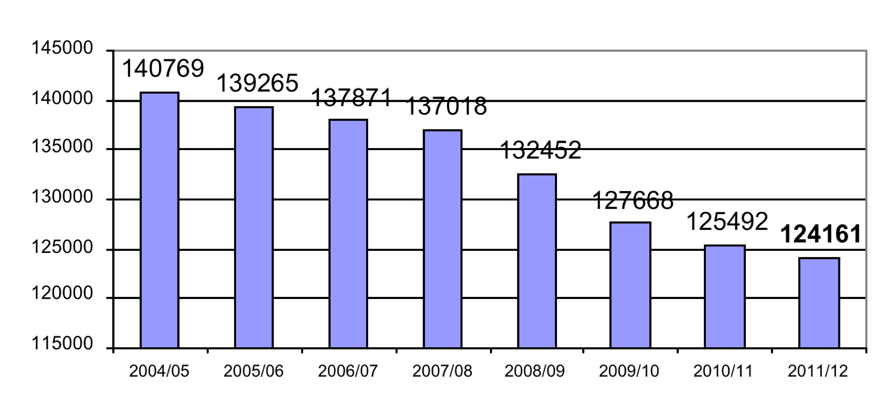

An outsider, who is basically unaware of education problems in Belarus, may conclude that the situation is not too bad, especially if the official statistics are looked at. The number of secondary schools is decreasing (Fig. 1), which is more likely caused by the demographic factor, rather than socio-cultural or administrative issues. It naturally leads to a partial teaching staff reduction, and, in general, this process seems to accelerate (Fig. 2).

The number of students of vocational and specialized secondary schools is also decreasing, yet insignificantly. The figures are smoothed to a certain extent by the higher education statistics as the number of university students is still increasing (Fig. 1). However, it will not last long given that most university applicants are secondary school graduates.

Source: Main Information Analytical Center (MIAC), Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus, 2011

Government experts report that everything is going well and the system is being upgraded. The question is what exactly education functionaries mean. Is an increase in the number of students an advance? Does the upgrade have an effect on reforming of secondary and higher education? It is more likely about stability that the authorities strive for, rather than development. But what is the price of this stability?

Source: Main Information Analytical Center, Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus, 2011

In 2011, this issue topped the agenda, first of all in terms of finances. In October-November, practically all universities raised the price of education up to USD 1,000 to 1,500 a year on average. The Ministry of Education said the tuition fees for the second through the fifth years were raised by no more than 20%.1 The money was supposed to be used to pay teachers and improve the universities’ infrastructure. It is notable that the cost of training was reconsidered after contracts with applicants had already been signed. It caused serious problems for many families, although there was no considerable outflow of students. As always, people were supposed to find a way out by themselves. Some students tried to switch to correspondence courses, which are cheaper than full-time attendance; many drew upon credits or looked for jobs.

As never before, the economic recession uncovered the inadequacy of the education funding model. The reform carried out in the 1990s did not remedy the core problem of the command-and-control management style: education managers are unready or reluctant to work out flexible funding models based on acquisition of incomes from multiple sources instead of getting the money from tuition fees and on-budget subsidies.

According to the national statistics, in 1998-2004, the education expenditure was between 6.1% and 6.6% of GDP. In 2005-2010, spending for education was down from 6.4% to 5.1%. It made up 8.9% in 2009 down from 20% in 2002 in general state expenditures.2 According to the Ministry of Education, the state spent nearly 7.2 million Belarusian rubles3 in 2011, an estimated 40-70% more than in secondary school.

The most part of the money goes for teaching staff salaries although they have always been lower than wages of industry workers accounting for 75% to 85% of the average level across the country. The government spends big money to pay vocational school and university students’ scholarships but they still make up 43% to 70% of the subsistence minimum.

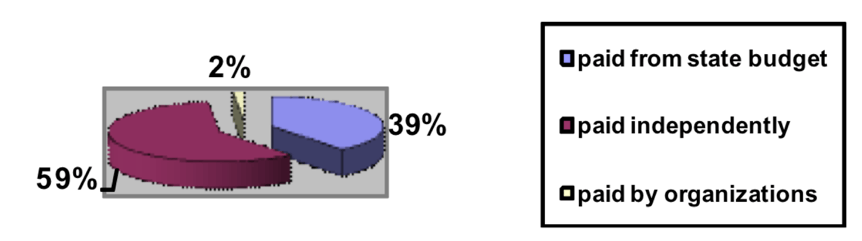

Households contribute generously to financing the education system, and they have been spending more and more in absolute terms since 2000. Education was responsible for 1.9% of final consumption expenditure in 2010 which represents a major increase from 0.66% in 2000. The figure amounted to 1.7% of total consumer spending in the 3rd quarter of 2011.4 State universities generate most of their incomes from education fees (Fig. 3).

Source: Main Information Analytical Center (MIAC), Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus, 2010.

Due to their limited autonomy, education institutions are deprived of the opportunity to determine optimal funding models. Besides, the state expects returns and graduates who reject post-graduate job assignments are supposed to reimburse the cost of their education.5

The education expenditure trends show a decline in financing of this sector. It is however not critical for now and does not induce the government to carry out structural reforms or make comprehensive changes in education institutions’ activities.

The education sector obviously experiences not so much an economic crisis as a thinking crisis. So far, education specialists cannot precisely distinguish education from training, i.e. comprehend the difference between higher education and higher vocational education which all other countries have defined. It is hard for them to understand what an education program is. All new terms are “adapted” to old ones.

For instance, the new Education Code interprets education program as “a body of documents which regulate the education process and conditions required for achievement of a certain level of basic education or a certain kind of extended education as expected by a recipient” (Paragraph 1 of the Code). But in fact, an educational program usually means an activity organized in a specific way aimed at providing education, training and eradication of illiteracy. Officials are going not to initiate new activities but to control documentation.

According to the Education Code, educational activities can be only carried out by organizations or entrepreneurs. It means that organizations, i.e. institutions, act as education actors rather than teachers, educators, methodologists and managers. But institutions cannot be actors by definition. The Code is full of such faulty interpretations. Can reforms really start with such fundamental law in this area which officials the present as a huge progress of the education legal framework?

Are there academicians in Belarus?

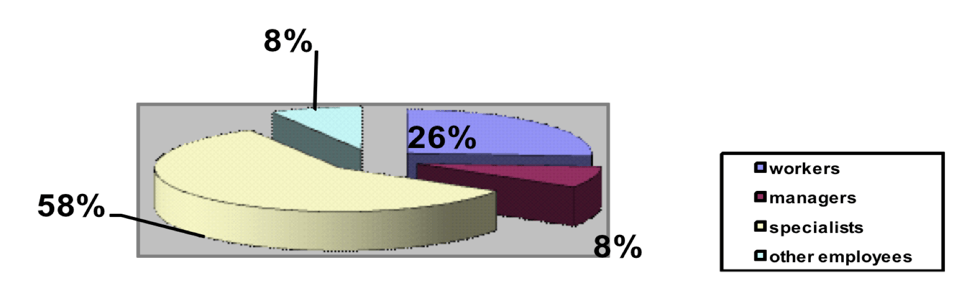

Here is one more, not less interesting question: is there an academic community in Belarus? There are educators and it can be proved statistically although the information about the number of education sector employees is sometimes inconsistent. As of late 2010, the number of employees stood at 443,500 or 9.5% of the total employed population. The data on the kinds of economic activities differ a little: education involves 458,300 people or 9.8% of the employed population. The NSC describes the qualitative composition of the education sector in a quite strange way. As a result, in late 2010, the total number of education workers amounted to 477,320 people. Which figures should we trust?

Source: National Statistics Committee: Labor and employment in Belarus, 2011.

No matter how the figures differ, the question of the academic community still stands. Even if the Code does not specify such entity at all, an academic community is an inevitable product of culture and history of the education system, because it is a prerogative of the academic community to establish universities and ensure quality of education in the country, while education officials are supposed to have another area of expertise. They can initiate a reform of the Academy of Sciences, give universities academic freedoms, etc., but it will be unsuccessful for sure because academicians should do it. Such sophisticated liberal institutions as scientific and academic communities with their commitment to the truth and reasoning cannot occur overnight and through administrative efforts only.

An open discussion and public communication on national concerns, problems of society as a whole and education in particular, an attempt to find common interests in the reforming of universities is what can trigger the process of evolution of the education actors. In 2011, this start was made not by the system of official education institutions, but informally, through the Flying University program and a series of simulations.6

Bologna Process: lost in translation

The government regards the export of education services and searching for extra funding sources as a tool for solving economic problems. The domestic market of educational services has been exhausted and, according to population forecasts, there will be fewer secondary school graduates to apply for admission to universities. Belarus needs its diplomas to be recognized outside the country and updated marketing technologies to approach foreign markets, which means adoption of the Bologna system of standardization and recognition of education quality.

In 2011, after long hesitation, the Ministry of Education headed by new Minister Sergei Maskevich started preparation for accession to the Bologna Process. Experts of the Republican Institute for Higher Education and TEMPUS7 Program were in charge of the technical component of joining the Common European Higher Education Area. Belarus officially applied to the Bologna Process Secretariat in November 2011.8 Although all technicalities seemed to be worked on diligently, politics came to the front. Education Ministry officials turned out to be unable to enter into political relations. They were frightening with politics, taking offence at politics, and making believe that education should have stayed away from politics.

It will suffice to mention that rectors of Belarus’ leading universities were banned from the European Union for expelling students after the events of December 19, 2010 for taking part in peaceful protest actions. There is also an unofficial employment ban for disloyal teachers. The problem of poor quality of education will simply pale into insignificance amid these scandalous repressions. Belarus’ accession to the Bologna Process in 2011-2012 would mean legitimization of the current sociopolitical relations in the country and their recognition by an outside authority. Belarusian officials publicly declared that accession to the Bologna Process would not require any alteration of the higher education system, which was certainly not true.

As a counter to the official viewpoints, a number of independent scientists and experts led by Professor Vladimir Dounaev initiated preparation of an alternative report and a road map for Belarus’ integration into the process. The Public Bologna Committee formed on the basis of the National Platform of the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum vocalized their position in December 2011: the education system of Belarus needs not only profound reforming of its structure, new management approaches and education quality, but also (first of all) depoliticization. Students must not be expelled and teachers must not be dismissed or threatened with dismissal on political grounds.9

In early 2012, a working group of the Common European Higher Education Area Secretariat heard two reports, the official and alternative ones, and recommended to postpone admittance of Belarus to the Bologna Process for noncompliance of the Belarusian education system with basic values of European education determined by academic freedoms, university autonomy and real students self-administration that does not deny technical aid to Belarus in the field of education and involvement in European programs like TEMPUS, ERASMUS, etc.

Conclusion

The economic (as well as the conceptual) crisis of education can be handled with the help of a long-term anti-crisis program. However, there are no signs that the government does anything to work out such program. As a matter of fact, problems are being glossed over instead of their objective recognition. It may be safely suggested that the crisis in education will get worse. Politics and economy will overshadow education issues for a while and backing out of reforms will result in lagging behind in humanitarian development even more and further alienation from European values and standards.

The situation with accession to the Bologna Process could be improved through dialogue between the academic community, civil society and authorities but, most likely, the government will keep playing out the scenario of evolutionary development imitation. Seeking reinforcement of its position, the government will look for loyal allies in the academic and expert communities, civil society and international institutions.