The WWW as a Habitat

Marina Sokolova, Mikhail Doroshevich

Summary

The active development of infrastructure, along with cheaper Internet access following the devaluation of the national currency, were some of the main prerequisites for the increase in numbers of Belarusian Internet users. As of December 2011, the Internet audience was 51% of the population over 15 years of age. Now there are more opportunities for “online activity”, the Internet is no longer just a platform for “online media” and is becoming a virtual habitat for society.

2011 was marked by the development of various types of online activism (crowd-sourcing, flash-mobs, Twitter, and other rapid means of distributing information and coordinating activity). Interaction between state bodies and citizens (e-government) is being included on the political agenda, as well as managing Internet use and development. Institutional and legislative initiatives in these fields are typified by:

- a technocratic approach (focusing on infrastructure development);

- ignoring the Internet’s global nature and being convinced that not only physical infrastructure, but also websites can be fully “locked” inside the state borders of Belarus;

- a desire on the part of the executive branch and law-enforcement bodies for total control over citizens’ online activity and business;

- a disregard for partnership opportunities with the business community and civil society.

Although taking certain steps to fight cyber crime, the Belarusian authorities are not paying sufficient attention to the protection of personal data and the inviolability of people’s online privacy. Moreover, censorship and other restrictive measures controlling Belarusian citizens’ use of Internet resources and services (including by violating users’ rights) are still common aspects of government policy.

Trends:

- The number of Internet users is increasing thanks to the active development of infrastructure and cheaper Internet access following the currency devaluation.

- There is still a digital gap: unequal Internet access opportunities for people from Minsk and its surrounding region as opposed to other regions of the country; most users have a higher education; and only an insignificant number of users are over 55.

- Websites are becoming more important as information sources, while interest in dedicated news sites (various types of traditional media) is dropping, and the audience of social networks is increasing.

- There are more active cases of online political and civic activism.

- The field of regulatory activity is dominated by the development of national telecommunications infrastructure, the computerisation of state management bodies, censorship and other restrictive measures controlling the use of Internet resources and services.

Infrastructure development and audience growth

The leading role in the development of telecommunications infrastructure to provide Internet access is played by the state communications operator Beltelecom, which still has the monopoly on the outer channel, i.e. access to the Internet. In 2011, the bandwidth of the Internet’s outer channel almost doubled, reaching 200 Gbit/s by early 2012: 50 Gbit/s (20 in early 2011) towards the West, and 150 Gbit/s (90 in early 2011) towards Russia.1 Since February 16, 2012, Beltelecom has been a client of the DE-CIX commercial Internet exchange in Frankfurt am Main, one of the leading international providers.

These resources ensure the operations of Beltelecom and secondary providers (58 in total).2 Furthermore, the state operator uses outer channels to offer international data transit services to Russia and Europe. An agreement on data transfer (“transit traffic”) using infrastructure located inside Belarus has been signed with telecommunications companies from Russia (Sinterra, Rostelecom and TransTeleCom) and Poland (Hawe Telekom). In 2011, the amount of data streams transiting via Belarus rose from 37 to 105 Gbit/s (more than 2.5 times),3 thus surpassing the total bandwidth for Belarusian citizens’ Internet access towards the West.

Beltelecom controls 78% of the broadband access (xDSL) market, and is the major Belarusian hosting provider (seven data processing centres, or DPCs). The second hosting service provider, DataKhata, opened its only DPC in Minsk in June 2011.4 Due to the obligatory requirement that companies and organisations offering services must be hosted within Belarusian state borders, the national data processing centres were periodically unable to handle the load, which resulted in Internet outages around the country.5

The network of Wi-Fi hotspots belonging to Beltelecom (which has almost monopolised service provision) more than doubled over the year: from 500 in February to 1100 in December. However, the percentage of users of these services decreased threefold.6 Experts explain that this sharp drop in the Wi-Fi market (along with a reduction in the number of Internet cafés) were “unpleasant consequences of Decree № 60”, which requires data to be stored concerning users and services provided to them.7 The reduced number of Wi-Fi users is also an alarming trend because the under-use of free Wi-Fi access points is a serious barrier to solving the problem of digital inequality.

One of the most important trends of the previous year was the growth in the number of broadband (xDSL) and high-speed mobile 3G (UMTS) users. After December 1, 2011, the Russian company Yota started offering trial mobile Internet access using 4G (LTE) technology.

| Connection type | December 2010 | January 2012 |

|---|---|---|

| Broadband access | 49.3 | 62.5 |

| Modem connection (dial-up) | 18.7 | 8.5 |

| Mobile connection | 5.6 | 11.36 |

| Wi-Fi | 3.1 | 1.2 |

In 2011, around 17 000 new .BY domains were registered (4000 more than in 2010). By the end of 2011, there were a total 44 000 of them. For the first time, physical entities started to register more domains than legal entities. This was mostly thanks to a fourfold decrease in the cost of domain names in the .BY zone – from USD 43 to 11 – as a result of the devaluation of the Belarusian rouble.9

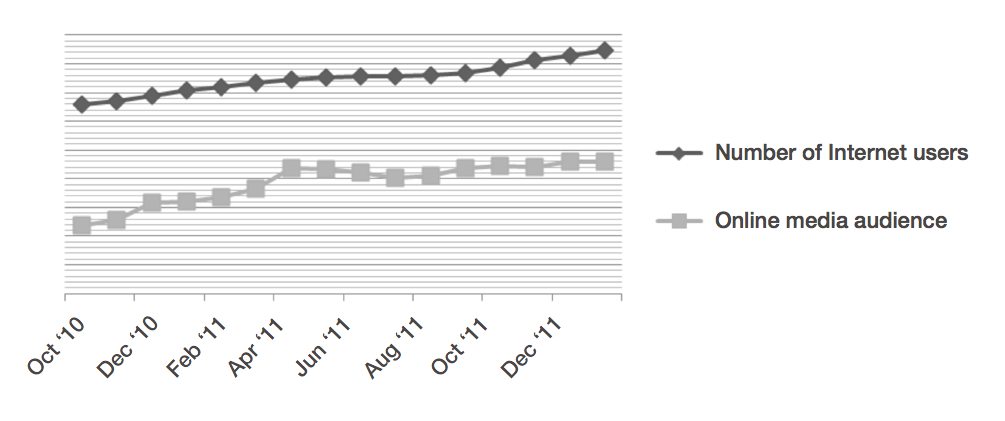

The active development of infrastructure, along with cheaper Internet access following the devaluation of the national currency, were some of the main prerequisites for the increase in numbers of Belarusian Internet users. In 2011, the Internet audience grew by 20%, reaching 4.144 million people in December (51% of the population aged over 15). The country occupied third position (after Ukraine [44% growth] and the Russian Federation [30% growth]) in ratings for Internet audience growth in Central and Eastern European countries.

In terms of the number of Internet users, Belarus climbed to 12th place, overtaking not only Ukraine, like last year, but Russia too. Most people (76.4%) use the Internet on a daily basis, mostly from home (91.2%). However, there is still a digital gap: unequal access opportunities for people from Minsk and its surrounding region as opposed to other regions of the country; most users have a higher education; and only an insignificant number of users are over 55.10

Use of Internet resources and services

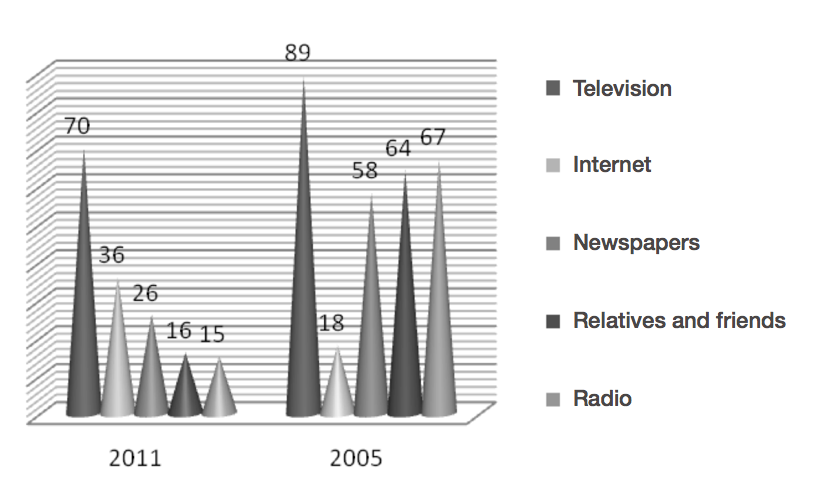

As in previous years, 2011 was marked by websites becoming more important as information sources. This general trend is noticeable if compared to 2005 (see Fig. 1). Notably, this growth in popularity is comparable to the more than twofold increase in the Internet audience over those six years.11 Television still has the largest audience, however. Print media have also maintained fairly stable positions, although there are hardly any periodical publications which do not have a “digital supplement” such as a website, social network presence, etc.

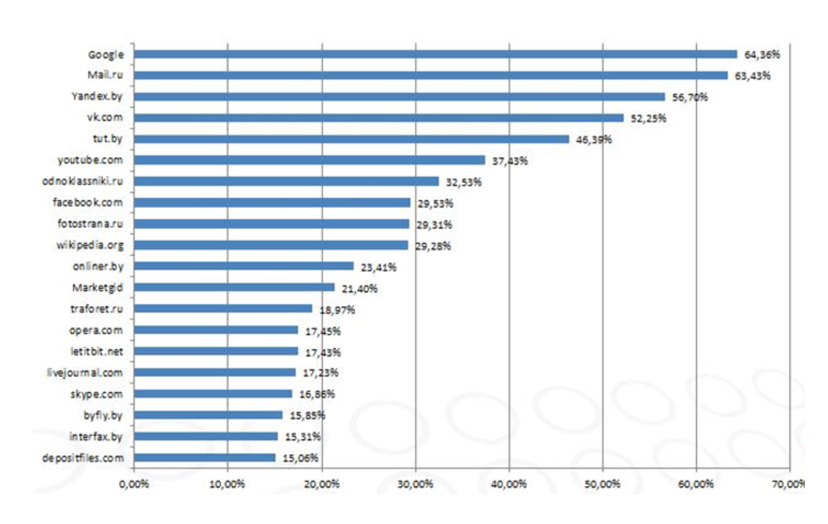

Another important trend was reduced interest in dedicated news sites (various modifications of traditional media), accompanied by a growth of social network audiences (see Figs. 2 & 3).

Approximately 2.8 million Belarusian Internet users (or 69.77%) log into social networks. vk.com still has the largest reach, as well as the largest number of registered users (2.1 million people, or 53.31%). In second place is odnoklassniki.ru (1.25 million, or 30.85%), and in third place is facebook.com (1.18 million, or 29%). Although not the largest, LiveJournal has the most active audience in Belarus (649 000 people, or 15.98%) – almost 96% of LJ users have also joined at least one other social network. Most social network users are young people (aged 15–24), of which there are more women than men in all age groups except 19–24 and over 55.15

Therefore, Belarusian users are also part of the process of the changing configuration of the online media landscape. The essence of this change is that new ways of “using information” and the convergence of media are leading to the previous division between “professional journalism” and “user-generated content” being replaced by network topology based on the specifics of individuals’, communities’ and organisations’ online activity.16

Furthermore, with the increased audience and more opportunities for “online activity”, the Internet is no longer just a platform for “online media” and is becoming a virtual habitat for society. Consequently, it is not surprising that 2011 was marked by the development of various types of online activism (crowd-sourcing, flash-mobs, Twitter, and other rapid means of distributing information and coordinating activity). This was particularly true of protest activity: the “Social Networks Revolution” and “Stop-Petrol” campaigns organised via social networks during the summer; using the “collective consciousness” (crowd-sourcing) to identify the people who smashed the windows of Government House on December 19, 2010; Internet petitions; a virtual postcard service for writing to Belarusian political prisoners; sites to help relatives and friends of those arrested to coordinate their activity, etc.17

Civic initiatives are also becoming more noticeable. The best example of this is the BelYama website, a social platform to gather information about road surface defects and apply “legal pressure on the relevant bodies in order to eliminate those defects” (http://belyama.by).

Institutional and legislative initiatives

The increased number of Internet service and website users, and the variety of opportunities for “online activity” are drawing more government attention to this field. Issues of interaction between state bodies and citizens (e-government), as well as managing Internet use and development, are being increasingly included on the political agenda.18 In 2011, four important pieces of legislation were passed:19

- A national programme for the rapid development of services in the field of information and communications technologies from 2011–2015 (Belarusian Council of Ministers resolution № 384 of 28.03.2011).20

- Presidential decree № 515 of 08.11.2011 “on several issues of developing the information society in the Republic of Belarus”.21

- Belarusian law № 308-3 of 8.11.2011 “on introducing amendments and additions to the Belarusian law on mass events in the Republic of Belarus”.22

- Belarusian law № 317-3 of 25.11.2011 “on introducing additions to the Belarusian Code of Administrative Contraventions and the Belarusian Procedural Enforcement Code of Administrative Contraventions”.23

The national programme anticipates extremely generalised measures for the development of telecommunications infrastructure, national content, and further development of e government projects. It is important to note that the term “private sector” is only mentioned in the “e government” subprogramme in relation to the possibility of transferring functions to third-party organisations (outsourcing). At the same time, according to World Bank experts, for most countries “with strong ICT strategies… the state’s function is seen as being to provide a platform by creating infrastructure and data sets which may then be used by the private sector to devise and introduce innovative solutions and applications”.24

The “formation of national content” subprogramme places its main emphasis on representing the positions of state bodies. “Creating unified technological conditions for the operation of Internet-versions of Belarusian media by uniting them via an aggregator on an Internet portal, and creating a ‘single entry point’ for state media on the Internet, will guarantee the effective representation of the positions of state bodies in the national segment of the Internet, including rapid response to newsworthy events”, the document reads.25

Presidential decree of № 515 “on several issues of developing the information society in the Republic of Belarus” stipulates the creation of a National Electronic Services Centre (NESC) and a Belarusian presidential Council for the Development of Information Society, as well as giving the Belarusian presidential News and Analysis Centre the functions of an independent telecommunications regulator. The structure and hierarchy of these bodies to be created in accordance with decree № 515 are such that they are all closely linked to the president.

To a large extent, the powers of the operator (NESC) coincide with those of the regulator, and both bodies have the full right to supervise data transmissions, but offer no guarantees of privacy or service quality. Moreover, as national regulator, the NAC has the right to recommend, negotiate and publish binding regulatory laws and legislative acts governing ICT, which 1) does not conform to the statute concerning the division between the legislative and executive branches, 2) contradicts the very principles of appropriate practice in the independent ICT regulation field.26

An article has been added to the Code of Administrative Contraventions regarding legal responsibility “for violating the law while using the national segment of the Internet”. There is also an amendment to Paragraph 2 of the law on mass events, which makes flash-mobs equal to picketing. A new article of the Administrative Code makes provisions for punishment for violations of Paragraph 2 of decree № 60. There is still no official interpretation of this paragraph, however. NAC representatives do not rule out broader interpretations, and advise people to enquire on a case-by-case basis.27 The main inconsistency concerns how to define responsibility within the limited “national” segment of the Internet.

Although taking certain steps to fight cyber crime,28 the Belarusian authorities are not paying sufficient attention to the protection of personal data and the inviolability of people’s online privacy. The law on information, computerisation and protection of information defines only general limits for this field. Meanwhile, the issue is becoming increasingly relevant as the implementation of projects progresses. After all, “as soon as a citizen has provided their data to an organisation, they are powerless to do anything with it. Legal responsibility for the security of the data is then borne by the organisation working with it, i.e. the personal data operator”.29 According to the results of a poll organised by NPT Ltd. (a company which integrates complex data security systems) and Kompyuternye Vesti in November 2011, only 28% of respondents replied yes to the question: “Does your organisation use systems to prevent information leaks?”. However, 47% confidently replied that their organisation has no such system. Only 12% of those polled stated that their organisation has a special information security department.30

The Belarusian legislature’s position is also unclear regarding the defence of copyright online. One of the few public statements on this topic was made by Denis Sidorenko, deputy head of the Belarusian delegation to the OSCE, who criticised the draft ACTA and SOPA bills, and expressed his agreement with the OSCE’s opinion about the need for serious discussion and thorough analysis of this topic “from the point of view of proper respect for human rights and basic freedoms”.31

During the period under review, no significant attempts were made to formulate principles for legal responsibility for information content placed online. Above all, no division was made between media and personal communication resources. In 2010, during his term as information minister, Oleg Proleskovskiy stated in an online conference: “Currently, Internet media are not officially considered to be media, and bloggers are not considered journalists”. He went on to say that this issue would be decided in a government resolution in 2011.32 However, the relevant regulatory acts have still not been passed. As a result, in summer 2011, a criminal suit was brought under Article 370 of the Criminal Code (desecration of state symbols) concerning Yevgeniy Lipkovich’s inclusion of a picture (“of an offensive and blasphemous nature”) of the Belarusian state flag on his blog lipkovich.livejournal.com.

Furthermore, the aforementioned amendment to Article 8 of the law on mass events in fact equates any Internet sites with media since it states that, until official permission to hold a mass event is received, the organisers “and other individuals do not have the right to announce in the media, Internet, or any other information networks the date, place and time it is to be held, or to prepare and distribute any flyers, posters, or other materials for that purpose”. Based on this amendment, the general prosecutor’s office issued a resolution on March 23, 2011 to limit access to the news sites charter97.org and belaruspartisan.org in all state institutions.33

The fact that censorship and other restrictive measures controlling Belarusian citizens’ use of Internet resources and services are still common aspects of government policy can been seen in statements made by prosecutor general Grigoriy Vasilevich and deputy presidential administration head Aleksandr Radkov in Autumn 2011.34 However, the problem lies not in access restrictions as such (which are essentially unavoidable), but in the fact that they are linked to non-compliance with current legislation.

The “general-access list of limited-access sites” section on the BelGIE site is still empty, although several social networks, the news sites charter97.org, belaruspartzan.org, spring96.org/ru, procopovi.ch, procopovich.net, and others are being blocked in state institutions (an unconfirmed report claims that the list contains about 60 sites). Means of restricting access which directly violate users’ rights (blocking sites, trolling, phishing, and identity theft) were also used repeatedly.35

A detailed analysis of Internet regulation and the implementation of e government projects in 2011 has shown that institutional and legislative initiatives in these fields are typified by: 1) a technocratic approach (mainly focusing on infrastructure development); 2) ignoring the Internet’s global nature and being convinced that not only physical infrastructure, but also websites can be “locked” inside the state borders of Belarus; 3) a desire on the part of the executive branch and law-enforcement bodies for total control over citizens’ online activity and business; 4) a disregard for partnership opportunities with the business community and civil society.36

Conclusion

The trends for active development of telecommunications infrastructure for Internet access will continue in the future, since this activity is one of the priorities set for national socio-economic development programmes. Consequently, the number of Internet users will also grow, even though the digital inequality (see above) will persist. Inappropriate regulation policy will lead to the country being left behind in terms of development and effective use of the Internet. There is a high probability that the desire to control citizens’ online behaviour and restrict access to Internet resources and services will continue by means of increasingly harsh legislation and illegal violations of users’ rights.